Photo by John Blair; courtesy of Dead Man's Line

On a frigid February morning in 1977, Tony Kiritsis walked into the offices of Meridian Mortgage in downtown Indianapolis with a grudge...and he walked out with a hostage. With a live television audience watching, Kiritsis paraded Dick Hall around the snowy city streets with a shotgun wired to the back of his head, and instantly captivated the nation.

Day 1 - February 8th, 1977

Kiritsis had worked with mortgage broker Dick Hall and his company for years negotiating real-estate deals for a piece of land on the west side of Indianapolis. However, it became clear that these deals were going nowhere and he quickly began to fall behind. Payments were missed, confrontations were made, and his resentment had finally reached a boiling point. In Kiritsis' mind, there was nothing left to do but to take matters into his own hands.

On the morning of February 8th, 1977, Kiritsis arrived at Dick's office looking for his father, M.L. Hall. When the receptionist informed him that Hall was on vacation, he changed his plan and instead walked into the office of his son, Dick. With one arm in a sling and a suit box under the other, Kiritsis walked into Dick's office ready to execute his plan. Upon opening the suit box, he revealed a sawed-off, double barrel shotgun. Kiritsis then attached a steel wire around Hall's neck that was tied to the barrel of the gun and connected to the trigger. Due to how tight the cable was, the barrel was pointed directly at the back Hall's head, creating a "dead man's line."

"If Hall or Kiritsis accidentally fell, the shotgun would go off. If Hall tried to get away, if law enforcement tried to intervene, or if a sniper shot Tony, the gun would disintegrate Dick Hall's head."

Mark Enochs - "The Long Cold Walk"

Once the death trap was assembled, Kiritsis used Hall's office phone to call the police. During the now infamous 50-minute-long call, he expressed his anger towards Hall and his father, explained the details of the situation, and gave his demands. During the call, he ordered a police escort out of the building and a getaway car waiting for him.

**Warning** This video contains mature language.

After hanging up with police, Kiritsis then forced Hall out of the office and down four flights of stairs. As the duo made their way out of the Meridian Mortgage building, they were confronted by a handful of police officers and stepped outside. Despite the near-frigid temperatures, Kiritsis directed Hall to walk west down Market St. with only the shirts on their backs to keep them warm.

While making their way downtown, it becomes clear to officers that Kiritsis is lost and turned around. What he failed to realize is that he and Hall immediately took a wrong turn by going west when they should have gone east towards a nearby parking lot where Kiritsis parked his car.

Waves of reporters from television and radio stations immediately made their way towards Meridian Mortgage after hearing about the situation on police scanners. At this point, Kiritsis was parading Hall aimlessly across downtown Indianapolis making multiple turns and frightening dozens of pedestrians with the contraption. Officers tried to negotiate with Kiritsis, but he only responded with heated threats and warnings for officers to keep their distance. Due to the limited amount of information that they knew at the time, all anyone could do was stay close behind and watch.

"Kiritsis demanded airtime. He got it and in doing so took local radio and television stations captive as well."

Tom Cochrun - "A Time of Hostages: A Reporter's Notebook"

Disaster nearly struck as the pair made their way across the city. While walking along the corner of Illinois and Washington St., Kiritsis stopped and began berating police officers that were following closely behind them. During his hate-fueled rage, he used his shotgun to swing Hall around towards the police. As he did this, he took an accidental misstep on the snowy sidewalk and stumbled towards the ground. Almost instinctively, Hall squatted down as Kiritsis was falling in order to avoid the steel cable around his neck from tightening and accidentally pulling the trigger. Miraculously, the gun did not go off, much to the surprise of police, Hall, and Kiritsis himself.

WTTV Indianapolis, Channel 4, coverage of the first day of the Kiritsis hostage drama, February 8, 1977.

After regaining their footing, the duo continued their way down Washington St. with police officers still following closely behind. On the corner of Washington and Senate St., an IMPD police officer had his patrol car parked in the middle of an intersection to help block traffic. The driver's side door was open and the engine was running inside. After stealing the officer's handcuffs, Kiritsis slowly backed into the cruiser and pulled Hall into the driver's seat.

During the chaos, one Indianapolis pedestrian got distracted by the sight and accidentally crashed their car into a telephone pole.

Kiritsis then turned on the cruiser's lights and demanded Hall start driving. With police in hot pursuit, Kiritsis navigated their way out of downtown and back to his home at the Crestwood Village apartment complex on the west side of the city where the remainder of the standoff would continue.

As soon as Kiritsis entered his apartment with Hall in tow, police and reporters immediately flooded the complex and began setting up a perimeter. Television media in Indianapolis at this time was in the beginning stages of a brand-new era. On top of radio stations bringing live updates on the situation, TV stations could now bring viewers up to date using brand-new live units.

Clips in this video

Early in the negotiations, police immediately realized the severity of the situation. Not only was Hall still wired to the shotgun, but Kiritsis had booby-trapped his entire apartment with homemade explosives that would trigger if the police tried to enter the unit or if snipers tried taking a shot at him. As police began evacuating the complex's residents, reporters began setting up camp inside apartments across the street from Kiritsis' building.

It was during these early negotiations where Kiritsis finally outlined his demands - airtime. His largest demand: he wanted a public apology on behalf of Meridian Mortgage to be broadcast live on the air. In addition, he wanted to talk with WIBC Radio News Director Fred Heckman in order to investigate and verify his claims that Meridian Mortgage had done him wrong.

Reporters had never faced this kind of dilemma before in Indianapolis' history. Kiritsis' demands immediately ushered in a new wave of moral questions for journalists to answer. Many journalists argued that the media should give into the demands and broadcast the message in order to save Hall's life. Those against this decision, however, argued that it would come at the expense of giving a potential madman full access and control over the airwaves.

"We were operating out of the apartment of a loyal WIBC listener who had evacuated, giving us her unit with a direct view of the courtyard, and the apartment where Kiritsis held Hall..."

Tom Cochrun - "A Time of Hostages: A Reporter's Notebook"

"...Things then settled down into an all-night stakeout and the arguments between reporters, editors, and police began. Should the media give into the demands, allowing an armed gunman to have live access to viewers and listeners? Some argued it was appropriate if it saved a life."

Day 2 - February 9th, 1977

At around 6:30 a.m. the next day, after a prolonged night of waiting for word from Kiritsis, WIBC News Director Fred Heckman finally reached Kiritsis on the telephone and began listening to his story. Heckman and other producers at the station ultimately decided to give into Kiritsis' demands and broadcast the interview live on the air, despite the station's inability to censor his foul language.

"It was a rant full of repeated obscenities that had likely never been broadcast in America. It was at this point that Heckman...was being drawn across the line from observer to participant."

Tom Cochrun - "A Time of Hostages: A Reporter's Notebook"

Once the broadcast concluded, Heckman became one of Kiritsis' main points of contact throughout the remainder of the siege. Unbeknownst to most of the police and the press, Kiritsis made frequent calls to Fred rather than talking to the negotiators outside his door. He would then broadcast these calls on the air to help meet his demands.

By the time the second day of the standoff began, the situation had turned into a national media story. Behavioral analysis experts from the FBI quickly made their way to the scene, along with the national media. Reporters from all across the world arrived in Indiana to give the latest details surrounding the situation, and Kiritsis took advantage of this.

When he was not on the phone with Heckman, he would tune into WIBC on his home radio to stay up to date on what the police were planning. On a number of occasions, he would hear about a potential plan to raid the apartment on the radio, and would immediately begin threatening Hall's life in order to get police to stand down.

Day 3 - February 10th, 1977

By Day 3 of the standoff, Heckman's role had evolved from journalist to a key player in the negotiations between Kiritsis and police. Once the FBI figured out how Kiritsis was getting his information, they decided to recruit the broadcasting veteran for help in diffusing the situation. He became the figure that everyone turned to - whether it be police or the media - for information regarding Kiritsis' mental state and the safety of his hostage.

Clips in this video

While Heckman began discussions with law enforcement, WIBC reporters began their own discussions surrounding how to cover such a historic event. WIBC reporter Tom Cochrun and his colleagues began wondering whether his involvement in the story would compromise the station's reporting. In the end, the team decided that Heckman, as their news director, could no longer have control over their coverage given his heavy involvement in the situation.

"In our impromptu ethics discussion, we decided if Heckman knew more than he could use on the air, he should abandon the story. We could use him as a source, but he should not direct our coverage plans. "Most of the reportage was unscripted. It required a critical judgement made on the run, and we believed that Heckman had been compromised by his own involvement in the negotiations and could not be fully forthcoming."

Tom Cochrun - "A Time of Hostages: A Reporter's Notebook"

Throughout the course of the third day, news outlets and police themselves began displaying a sense of optimism throughout the complex. However, many reporters believed this positive attitude was a ruse to try and change Kiritsis' mood about the situation.

After a long day of slow progress, Heckman relayed information that he believed negotiations would soon be over. According to officials close to the case, Kiritsis and law enforcement had reached an agreement where Hall would be released from the complex first, followed by Kiritsis who would be apprehended in the complex's courtyard.

As day turned into night, Kiritsis and Hall did emerge from the apartment. However, it was clear that Kiritsis had ignored the negotiations and changed his plan. As Hall exited the unit, he was still wired to the shotgun and Kiritsis followed closely behind him.

Reporters and police alike were quick to follow and soon gathered inside the complex's main office building where Kiritsis and Hall stood before an ocean of cameras, lights, and microphones, all broadcasting live.

At the exact same time, audiences tuned in to ABC were watching cinema legend John Wayne take the stage to present an award at an award ceremony when suddenly the feed was interrupted by a special report. Anyone unfamiliar with the case were then introduced with the shocking image of Kiritsis pushing Hall into the office.

**Warning** This video contains disturbing imagery and mature language

Kiritsis' impromptu press conference lasted over a half hour and was filled with profanity. Much like his original call to the police, Kiritsis expressed his anger towards Meridian Mortgage and made audiences at home aware of the wrongs that he endured. Along the way, he also made it a point to apologize for any trouble he had caused as well as his language that audiences were hearing.

All the while, reporters and police alike waited in anticipation for what he might do next. Many wondered whether Kiritsis' speech was a final goodbye before taking Hall's life along with his own. Surrounding Kiritsis was Fred Heckman and multiple police officials who had implemented a rescue plan in case things went awry.

At the end of his speech, Kiritsis marched Hall and multiple police officers into a side office where press were prevented from entering. After filing out of the office, the media began broadcasting follow-up reports on the events that had just occurred. Suddenly, everything was thrown into chaos.

BANG!!

The blast of a shotgun echoed throughout the courtyard of the complex. Reporters quickly began reassessing the situation.

"What just happened?" "Did Kiritsis just kill Dick Hall?" "Did police just kill Kiritsis?"

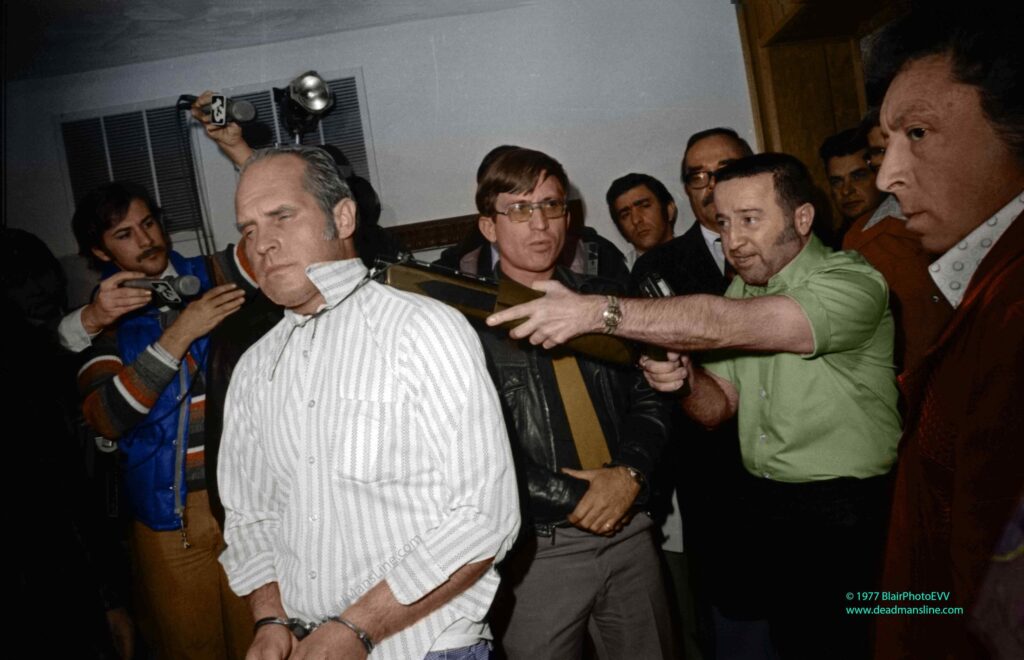

Soon after the blast, reporters were met with more answers, but even more confusion. Dick Hall made his way out of the complex, alive and well, surrounded by police officers and medical staff. However, soon after, Kiritsis, also alive and well, was marched out of the complex in handcuffs and in police custody. It was only towards the end of the night when reporters finally got the full picture.

Inside the office, Kiritsis had upheld his end of the negotiations. Upon entering the room, he began to disassemble the contraption and set Hall free. However, shortly after releasing his hostage, Kiritsis wanted to prove to officers that his contraption was the real deal. In order to prove his point, Kiritsis marched over to an open window with the sawed-off double-barrel and fired a shot into the sky. He was then quickly apprehended by officers.

As Hall headed to the hospital, and Kiritsis headed to jail, the media made their final reports on the situation and began to disperse. The bizarre situation was finally over, and by some miracle, no lives were lost.

Aftermath

In the months after the situation drew to a close, Kiritsis went on trial for kidnapping, armed robbery, and armed extortion. Kiritsis and his lawyers approached the case looking to draw an acquittal and submitted a plea of "not guilty by reason of insanity."

After months of trial and arguments, the jury was dismissed and returned with a verdict on October 21, 1977.

Not Guilty.

The verdict outraged many public officials and the general public alike. The result of Kiritsis' trial was so infamous that the state of Indiana later implemented a new plea of "guilty but mentally ill" for defendants to use during trials.

Due to his plea, Kiritsis was then turned over to the State Department for Mental Health and was committed to an institution. After serving 11 years in the institution, he was released. In January of 2005, Kiritsis died from natural causes at the age of 72.

Dick Hall wrote a book about his experiences titled Kiritsis and Me: Enduring 63 Hours at Gunpoint in 2017. In May of 2022, Hall died in his sleep "following a brief illness" according to his family.

The Tony Kiritsis hostage incident was one of the first instances where local journalists covered a live hostage situation; and it forever changed how these incidents were covered in the media. Journalists were on the scene almost instantly with their cameras drawn, despite the ethical question of whether the event should even be shown in audiences' living rooms. Years after the incident, legendary Indiana broadcaster Mike Ahern would say that stations never should have gone live. However, the cameras were rolling, and audiences were watching, and the events that unfolded over those 63 hours would forever change journalists' approach to live broadcasting.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

By Jack Lindner

Information courtesy of Dead Man's Line, "The Long Cold Walk," Indiana Historical Society, FOX 59, The Indianapolis Star, and Dead Man's Line documentary

Last Edit: July 2024